Spatial accommodating responses during plant development

Research in our laboratory is focused on understanding how the interplay between chemical signals and mechanical forces jointly regulate spatial accommodating responses during plant development. Osmotically-driven turgor pressure of plant cells can be higher than that of a car tire. It puts tremendous forces onto cell walls and drives changes in cell shape. This has given rise to unique mechanisms to control organ formation in comparison to metazoans. The fascinating interplay between forces and local cellular reorganization is poorly understood.

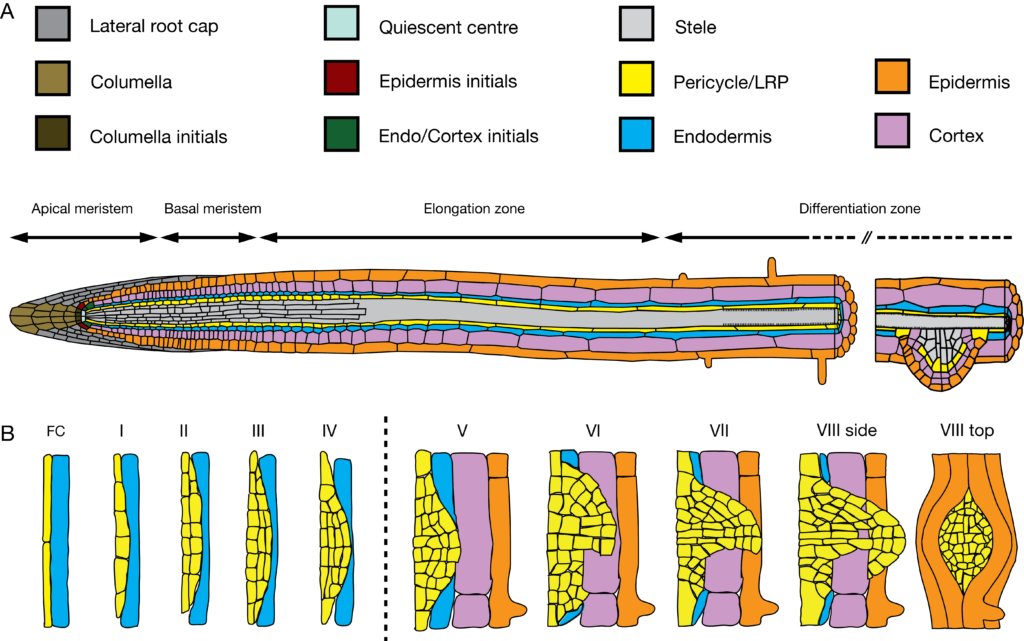

We use the formation of lateral roots as our experimental system, as lateral root formation is a prominent example of a developmental process in which mechanical forces between neighboring cells are generated. Lateral roots initiate in a single cell layer that resides deep within the primary root, the pereicycle. On its way out, lateral roots grow through the overlying endodermal, cortical and epidermal cell layers. We have demonstrated that in Arabidopsis thaliana, endodermal cells actively accommodate lateral root formation. Endodermal responses include a dramatic volume loss and a controlled degradation of their lignin-based paracellular diffusion barrier. Interfering genetically with these accommodating responses in the differentiated endodermis of Arabidopsis roots, completely blocks cell proliferation in the pericycle, and no lateral roots are formed.

Thus, the lateral root system provides a unique opportunity to elucidate the molecular and cellular mechanisms how mechanical forces and intercellular communication regulate spatial accommodation during plant development. In contrast to epidermal cells that respond to mechanical cues by restricting or allowing for expansion and giving support to the organ/plant, my experimental approach deals with the opposite as the overlying cell layers need to undergo controlled volume loss in order to accommodate growth of the newly-formed lateral root.

We are using genetic screens, state-of-the-art transcript profiling and advanced live cell imaging to identify the molecular players and mechanisms by which mechanical forces and intercellular communication regulate spatial accommodation. Beyond its importance for lateral root formation, this research will provide fundamental new insights into many other developmental processes that heavily depend on spatial accommodation by surrounding tissue. These include the growth of pollen tubes and infection threads, the development of sclerenchyma fiber cells or the intracellular accommodation of symbionts.

Model systems, such as Arabidopsis, have been and are still instrumental to understand diverse fundamental developmental processes. They form a reference for future studies and often provided textbook knowledge. However, some of the features that make them a good model, i.e. simple anatomy, small stature, and small genome sizes, do not always mean that they are representative for a given developmental process. Due to technical advances, i.e. novel sequencing techniques, genome editing and increased computational power, we now can expand the organisms to study development and introduce new ‘models’ to perform comparative studies. This will allow us to start elucidating which mechanisms are conserved and which are diverged or repurposed during a similar developmental process in different species. This certainly holds true for LR development and the associated accommodating responses. This is particularly relevant for the role of the endodermis during lateral root formation, as it is already known that in many plant species, the endodermis reactivates its cell cycle and appears to become integrated within the new organ, possibly by forming the root cap (Xiao et al., 2019, PMID: 31591087). However, we still lack understanding on the molecular mechanisms that regulate this de-differentiation of the endodermis.

In addition, many species contain an extra barrier cell layer, present in the most outer cortex cell layer i.e. below the epidermis: the hypodermis or exodermis. The latter term is applied when the hypodermis contains a localized lignification and suberin deposition in their cell walls with a similar barrier function as the endodermis. A recent, pioneering study has revealed that suberin deposition in the exodermis and not endodermis is important for drought tolerance in tomato (Canto-Pastor et al., 2024, PMID: 38168610). However, reports linking the exodermis to LR formation are still lacking.

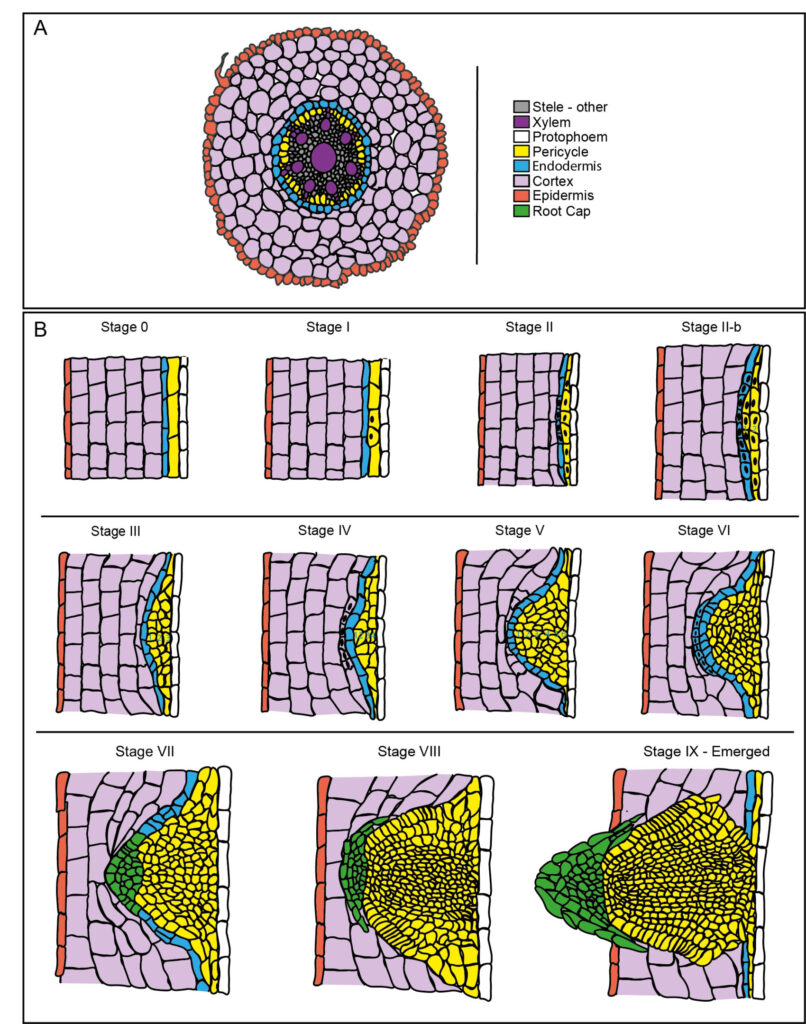

To address this we are also using the wild grass Brachypodium distachyon to better understand the molecular mechanism that regulates endodermis de-differentiation during lateral root formation. We have optimised root clearing protocols to use multiphoton microscopy to image lateral root developmen in Brachypodium. This resulted in an atlas of Brachypodium development (De Jesus Vieira Teixeira et al., 2024 PMID: 39158386).

Schematic representation of LRP development in Brachypodium. (A) Representation of root cross section of Brachypodium. (B) Successive stages of LRP formation are illustrated. From De Jesus Vieira Teixeira et al., 2024 PMID: 39158386.

We will use single cell sequencing, mosaic analysis and cell and molecualr biological approaches to elucidate the mechanism(s) underlying endodermis de-differentiation during lateral root formation. Subsequently, we will test whether the identified mechanisms are conserved in other species in which the endodermis also undergoes a similar de-differentiation process.