Research

Plants are extremely plastic organisms. Throughout their development they change the number, shape and functionality of their organs depending on the environmental conditions. Our research focuses on the developmental changes in the aerial part of the plant in response to light and temperature signals, using Arabidopsis thaliana as a model species.

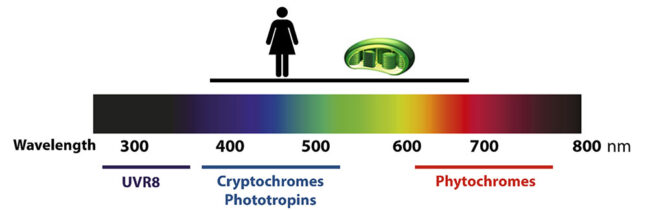

Light is among the most impactful and dynamic environmental conditions. As photoautotrophic organisms, plants use light as a source of energy through photosynthesis. In addition, plants possess specialized receptors which perceive light signals that provide information about the time of the day, the season, and the plant’s position with respect to the soil surface or other plants. These photosensory receptors perceive specific wavelengths, and belong to five main families: UVR8 perceives UVB light, cryptochromes and phototropins perceive blue light, and phytochromes perceive red and far-red light (Figure 1).

Figure 1: center: solar spectrum. Top: visible light by the human eye, represented by a person, photosynthetically active radiation represented by a chloroplast. Bottom: families of photoreceptors indicating the range of wavelengths that regulate their activity.

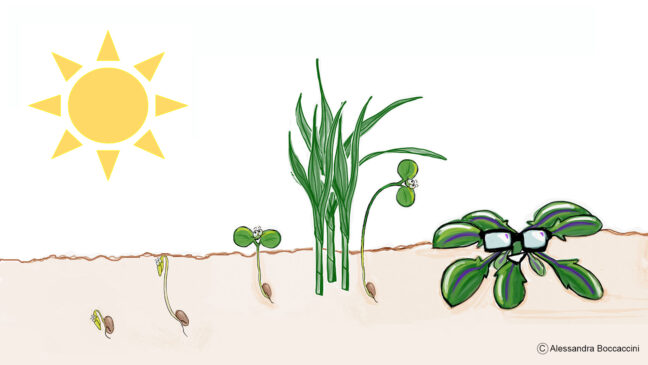

In response to light and temperature signals plants suffer extreme developmental changes, including changes in leaf anatomy and positioning [1, 2], hypocotyl and stem elongation [3-5], as well as regulation of flowering time and the branching pattern [6, 7] (Figure 2). The latter is the current focus of the lab.

Figure 2: developmental changes in response to light cues in Arabidopsis. Picture credit: A. Boccaccini.

Branches are formed by shoot meristems, groups of undifferentiated pluripotent cells that can divide actively and give rise to all aerial plant organs. In Arabidopsis the shoot apical meristem (SAM) will produce leaves until the induction of flowering, where it will start producing flowers and the main inflorescence. Meanwhile, in the axil of leaves (the upper part of the base of the petiole) the axillary meristems (AM) will start forming and producing a few leaves or leaf primordia to form an axillary bud. This axillary bud can remain dormant or continue growing to form an axillary branch. Shoot architecture will be largely determined by the regulation of axillary bud dormancy and outgrowth. In part this is regulated endogenously, because the shoot apex inhibits axillary branch development by a process called apical dominance (for more details on apical dominance regulation refer to [8]). But in addition to that, plants can regulate the formation of new branches depending on the environmental conditions, like light and temperature [9].

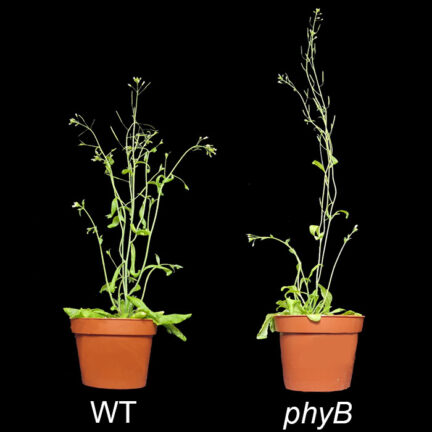

Among light signals, one that has a strong effect on branching is canopy shade. This signal arises when plants grow in close proximity: the photosynthetic tissues absorb mostly red and blue light and reflect and transmit other wavelengths. For example, they reflect and transmit green light, and because our eyes perceive green light, we see plants of this color. But in addition, plants reflect and transmit far-red, a color which is not visible by the human eye but can be very precisely perceived by plants through phytochrome light receptors. In the presence of neighboring plants, even before perceiving reductions in the photosynthetically active radiation, increases in far-red light are perceived by phytochromes, which reduce their activity and promote the so-called shade-avoidance responses. These responses increase plant’s access to sunlight and enhance the capacity to outcompete neighbors. In response to shade signals Arabidposis plants show enhanced stem elongation, changes in leaf positioning and anatomy, accelerated flowering and inhibition of branching [6, 7, 10] (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Shoot architecture of a wild-type Arabidopsis plant (WT) or a mutant plant lacking the phytochrome B photoreceptor (phyB).

In this regard, our aim is to gain insight on the molecular factors and hormonal mechanisms involved in shade-induced inhibition of branching, with a focus on the site-specificity of the signaling cascades.

In addition to shade signals, temperature also influences branching [9], but there have been very few experiments aimed at characterizing this response in Arabidopsis and describing the molecular mechanisms. However, in many other developmental responses such as hypocotyl elongation or leaf development, warm temperatures and shade signals show largely overlapping mechanisms [1, 6]. For example, phytochromes are not only light receptors specialized in shade perception, but also temperature sensors [11]. Thus, as a starting point we will use light signaling mechanism as a roadmap to start studying branching regulation by warm temperature, with the aim to identify the molecular signaling mechanisms underlying temperature effects on shoot architecture.

The above-mentioned aims are the current focus of the lab. However, we are open to evaluate other research directions related to photoreceptor signaling in plants or other environmental effects on shoot architecture, such as the activity of the shoot apical meristem or leaf development. Please feel free to reach out in case you would like to discuss your personal research idea.

- Legris, M., Light and temperature regulation of leaf morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist, 2023. 240(6): p. 2191-2196.

- Legris, M., Szarzynska-Erden, B.M., Trevisan, M., Allenbach Petrolati, L., and Fankhauser, C., Phototropin-mediated perception of light direction in leaves regulates blade flattening. Plant Physiology, 2021. 187(3): p. 1235-1249.

- Legris, M., Ince, Y.C., and Fankhauser, C., Molecular mechanisms underlying phytochrome-controlled morphogenesis in plants. Nature communications, 2019. 10(1): p. 5219.

- Legris, M. and Boccaccini, A., Stem phototropism toward blue and ultraviolet light. Physiol Plant, 2020. 169(3): p. 357-368.

- Nawkar, G.M., Legris, M., Goyal, A., Schmid-Siegert, E., Fleury, J., Mucciolo, A., De Bellis, D., Trevisan, M., Schueler, A., and Fankhauser, C., Air channels create a directional light signal to regulate hypocotyl phototropism. Science, 2023. 382(6673): p. 935-940.

- Casal, J.J. and Fankhauser, C., Shade avoidance in the context of climate change. Plant Physiology, 2023.

- Fernández-Milmanda, G.L. and Ballaré, C.L., Shade avoidance: expanding the color and hormone palette. Trends in plant science, 2021. 26(5): p. 509-523.

- Beveridge, C.A., Rameau, C., and Wijerathna-Yapa, A., Lessons from a century of apical dominance research. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2023. 74(14): p. 3903-3922.

- Fichtner, F., Barbier, F.F., Kerr, S.C., Dudley, C., Cubas, P., Turnbull, C., Brewer, P.B., and Beveridge, C.A., Plasticity of bud outgrowth varies at cauline and rosette nodes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiology, 2022. 188(3): p. 1586-1603.

- Finlayson, S.A., Krishnareddy, S.R., Kebrom, T.H., and Casal, J.J., Phytochrome regulation of branching in Arabidopsis. Plant physiology, 2010. 152(4): p. 1914-1927.

- Legris, M., Klose, C., Burgie, E.S., Costigliolo, C., Neme, M., Hiltbrunner, A., Wigge, P.A., Schäfer, E., Vierstra, R.D., and Casal, J.J., Phytochrome B integrates light and temperature signals in Arabidopsis. Science, 2016. 354(6314): p. 897-900.