Research

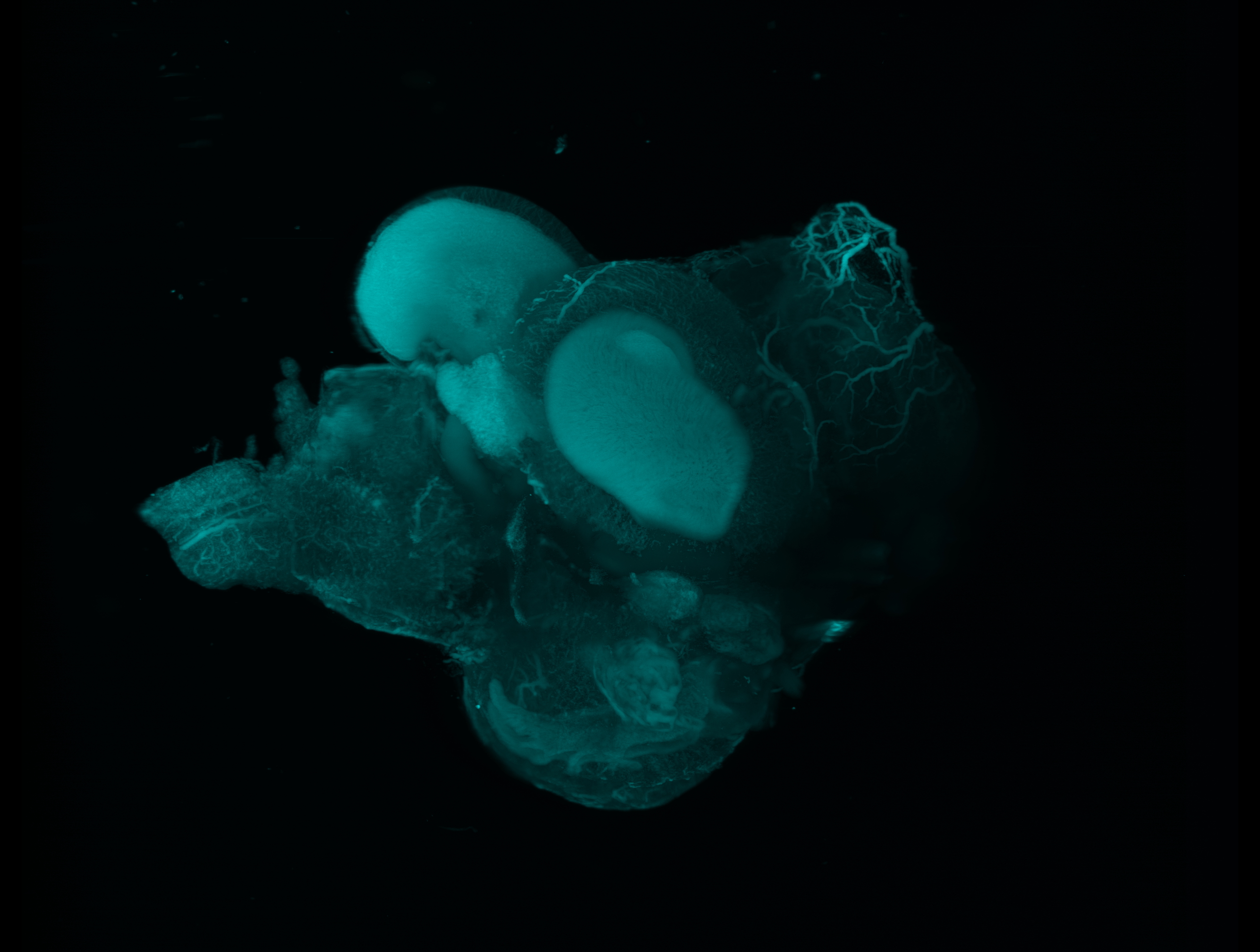

African Cichlid research

As the main component of the nervous system, the brain is the centre of information perception, processing, storage, and decision-making. Growing and maintaining neural tissue is, however, energetically costly. In humans, for instance, each brain tissue unit needs about 22 times the amount of metabolic energy used to maintain an equivalent unit of muscle tissue. Growing a brain is thus constrained by the individual’s total energy budget. There is a potential existence of an energy trade-off manifested by a selective energy investment in the brain. The depleted energy for brain use can, as a result, have some consequences for other expensive tissues and functions, e.g., the gut, liver, immunity and growth. In collaboration with Barbara Taborsky from Unibern, we are using a freshwater African cichlid fish, Neolamprologus pulcher, to study the trade-offs between investment in expensive tissues and cognitive abilities within species. We are combining various methods and techniques from different disciplines to unravel how and when individuals allocate energy to develop more complex brains and what are the subsequent cognitive benefits.

Sex-changing fish species

Sexual selection theory posits that traits such as bright colours and larger size increase mating success in males, often resulting in pronounced sexual dimorphism, where males are competitive and females are choosy. Cognitive processes play a key role in shaping behavioural strategies related to reproduction, which may lead to differences in the cognitive mechanisms between the sexes. To explore these questions, we are studying sex-changing species, which provide an ideal system for examining the interplay between biological predispositions and environmental factors. In sequential hermaphroditism, found only in fishes among vertebrates, individuals first reproduce as one sex—male in protandry or female in protogyny—when they are young and small, and later switch to the opposite sex as they grow older and larger. This sex change involves significant gonadal, physiological, and neural transformations. As a result, individuals must navigate the unique social and environmental challenges associated with each sex throughout their lives, adapting their life history strategies as they transition from one sex to another. These species offer a unique opportunity to examine how cognitive and brain morphological differences emerge in response to both nature and nurture.

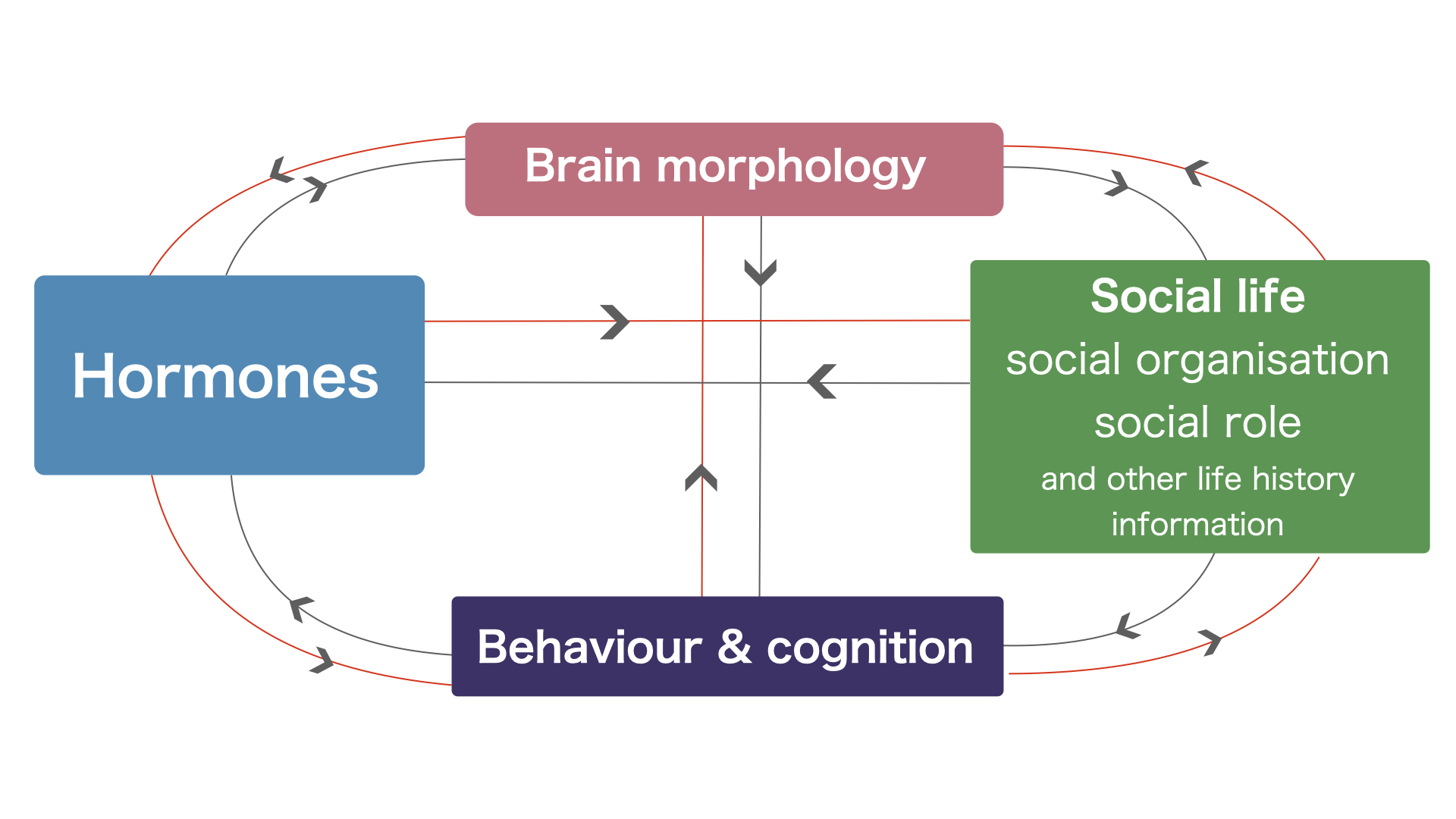

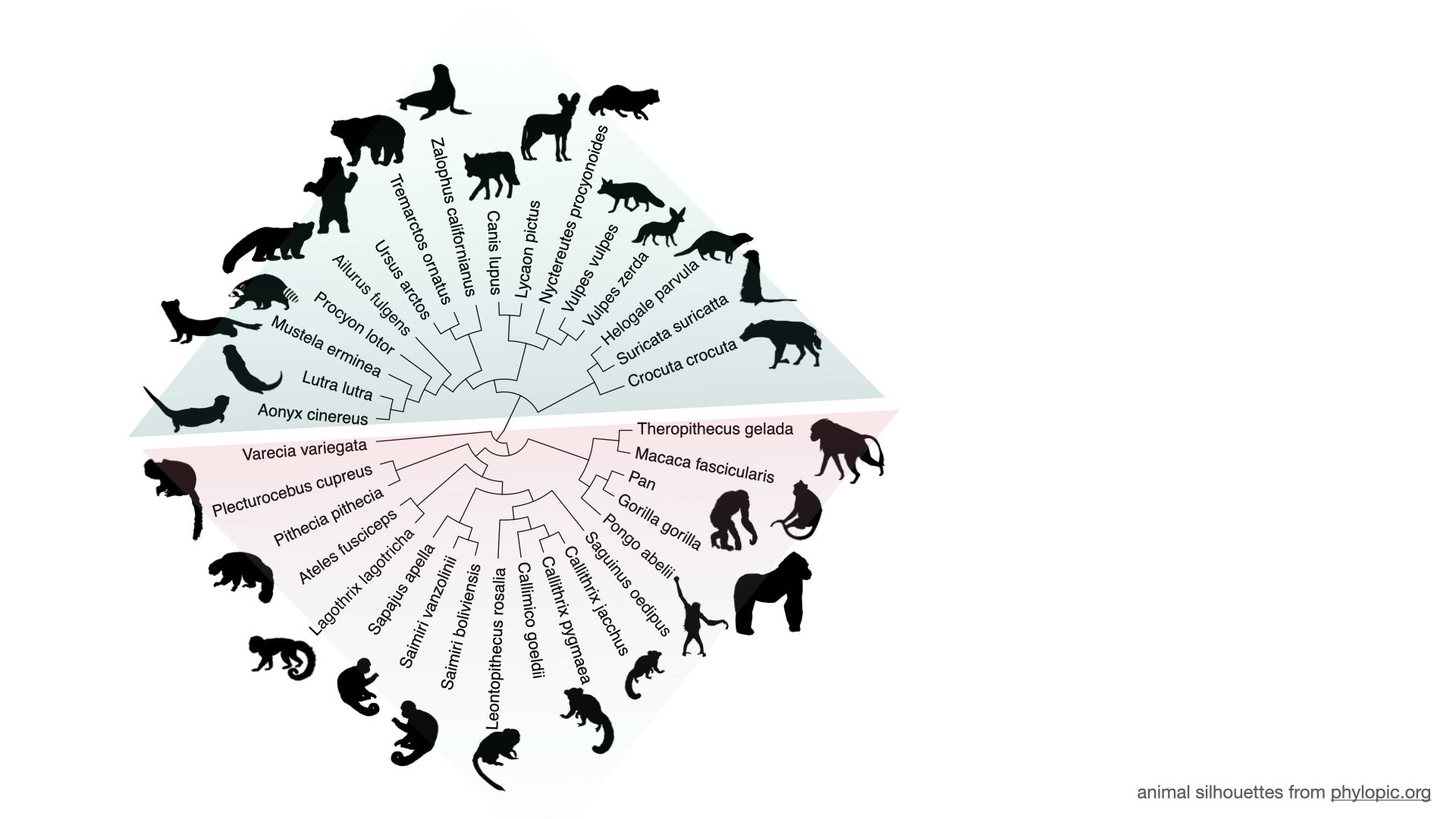

Swiss zoo animals research with the NCCR Evolving Language

In collaboration with Klaus Zuberbühler and the team within the NCCR Evolving Language network, we are conducting research in Swiss animal zoos to explore how hormones influence competitive and cooperative communication based on species’ social organization. Our goal is to combine physiological measurements with behavioural observations to investigate how social systems shape communication needs, which in turn impact physiology and lead to adaptive behaviour. By examining the communication contexts and frequency across various species, we aim to understand how hormones modulate communication and how cooperative breeding influences the richness and use of the communication repertoire. This approach will allow us to expand our understanding of how physiological parameters and behaviour interact to shape competitive and cooperative communication across species.

“The fish challenge to vertebrate cognitive evolution”

In collaboration with Carel van Schaik and Redouan Bshary, we are investigating the fundamental differences in brain allometry between endotherms and ectotherms, with a particular interest in the remarkable tenfold difference in brain size between these two groups. While many studies focus on identifying the ecological factors (such as social and environmental influences) that explain brain size variation within taxa, a more fundamental divide exists between endothermic and ectothermic vertebrates. Ectotherms, on average, have brains that are ten times smaller than those of endotherms. Existing hypotheses struggle to explain this divide, especially since some endothermic species with relatively simpler social structures and diets still possess larger brains. Additionally, research shows that certain ectotherms, particularly fish, possess a cognitive “toolkit” comparable to that of many endotherms, posing the “fish challenge” to vertebrate cognitive evolution.

Photos credit: ©SimonGingins; ©CocoLebet; ©ZegniTriki